How to Use This Game Guide

From

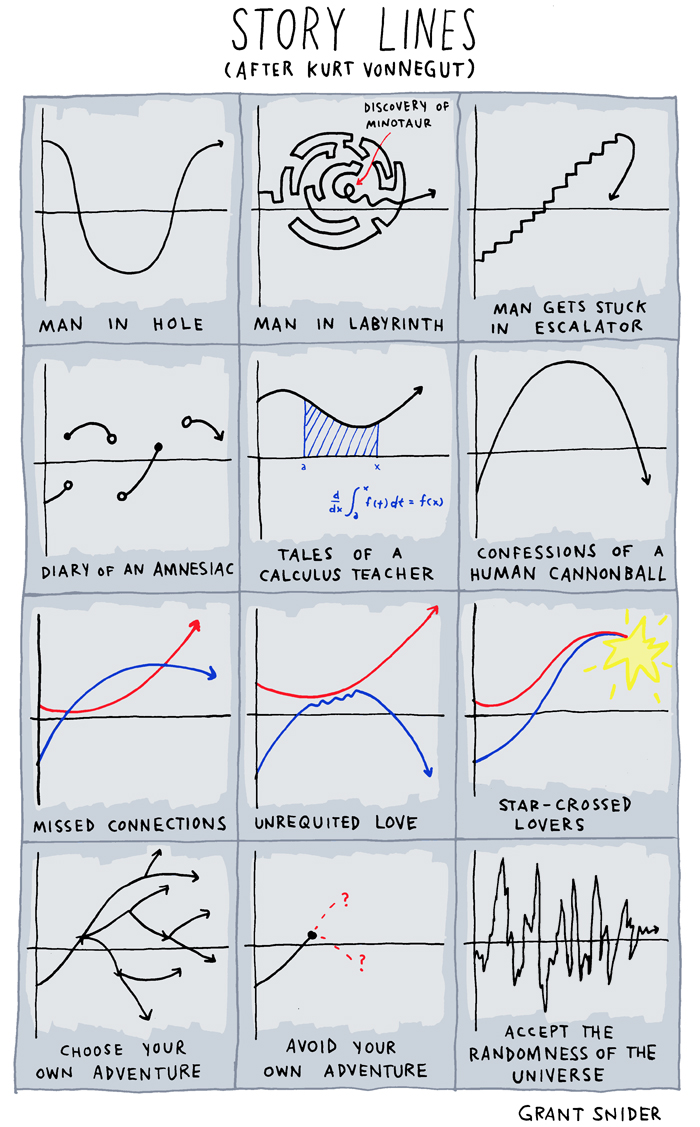

Unlike ourstories callin today:just one Genre, the story of Samara is one of unity and emerging clarity, but it is also of diversity. This journey has seen many storylines. See the few below, which have all played out in different ways.

Joining a DHO should really start with an experience of Star Crossed Lovers. Why? Because if purpose is the pull, the resonance is there and we truly care... then we need to find a meeting of the heart. In Samara's case this was many hearts with a beautiful shared sense of something beautiful and unformed. For other founding pioneers, there may be a very different attraction, but that basic heart connection is what seems to have started the real commitment that subsequently emerged and is needed to initiate a DHO. As any lover knows, being Present and being Patient and letting the unformed beauty emerge is an important pattern to nurture in any relationship. That is the kind of space and environment we saw being upheld in Samara as the activities and intentions weaved together into something more distinct.

JS - notes on thinking about structure:

- Should we create a story line for the Game Guide (see below)

- Should we adopt a novel format (e.g. beginning, middle, end and tension points?)

- Personally love the last three archetypes below :)

-

Learn the pros of different story structure types

Three act structure: the story can be divided into three parts. Classic novels of voyage and return, for example, often follow this structure. Randy Ingermanson breaks down this structure in fantasy series such as Harry Potter and Twilight

Orson Scott Card’s 4 story structures: In a post for Writer’s Digest, Orson Scott Card details four story structure types according to the plot details authors structure stories around. They are:

a) The Milieu Story: An observer who sees things the way we see them experiences a strange place (e.g. Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz) – the story is structured around the experience of a strange and outlandish setting.

b) The Idea Story: A question is raised and answered (e.g. in mystery novels, the central questions ‘who’ and ‘why’? Who was the killer and what was their motive?

c) The Character Story: A character goes through immense inner change, and this is the story’s main focus. Coming-of-age novels, such as James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) typify this structure.

d) The Event Story: Something is wrong with the world and either a new order must be established or the old must be destroyed. The Lord of the Rings, in which the tyrant Sauron must be stopped, is a classic example.

Mirror structure: In David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas (2004), each section of the book is left incomplete until the book’s central section. From there, Mitchell resolves the unfinished character arcs in reverse order, ending with the first character’s arc and settingKnow how to structure a novel to suit your central idea

When you decide how to structure a novel, think about your central idea. What would best suit your story type?

A story, for example, about an adventure and return home (like The Lord of the Rings or Homer’s Odyssey) might suit Three Act Structure because of the simple three-part narrative arc: ‘home – away – home again’.

Think about the mirror structure of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas described above. The novel begins with diary excerpts by a sailor living in 1850. The middle section follows a different character. It could be set in pre-modern times, following tribal life, but we slowly realize it might describe a post-apocalyptic future, a return to tribal life wrought by conflict or disaster.

In Cloud Atlas, the idea of history being cyclical – of returning to the beginning and starting over – is everywhere. We see it in both the changing time-frame of the story and how its individual chapters circle back to previous, unfinished story arcs. The mirror structure of the book is thus perfect for showing cyclical, repetitive elements of history – how society builds itself up and tears itself back down to start all over. -

Think how you can structure your story so that the structure itself – the ordering of scenes, time-frames and events – creates meaning. It would make sense, for example, for a novel where the protagonist has amnesia, to include structural holes and gaps. You might have ‘missing’ chapters the story later fills in. Allow yourself to play with structure as you would with setting and characterization. Have fun with it.